Increased Metabolic Diversity and Efficiency

In natural habitats, as opposed to simplified laboratory systems, the available nutrients are often complex polysaccharides, proteins, glycoproteins or other relatively refractory materials. It is unusual for any one microbial species to have the metabolic capacity to completely metabolize such complex substrates. Complete microbial communities are composed of pairs or larger collections of microbes with complementary enzyme profiles which are collectively capable of metabolizing complex substrates ultimately to such metabolic end-products as CO2, CH4, H2 and H2S. In this process it is typically the case that the metabolic product of one community member becomes the substrate of another. In fact the consumption of such end-products may be essential for the continued growth of both species.

One classic example involved the isolation of a methane-producing microorganism called Methanobacilus omelianskii. This anaerobic methanogenic "bacterium" reduced ethanol and a few other substrates such as n-propanol, n-butanol and pyruvate to methane. It was not until 11 years after its discovery that investigators published the fact that what they had assumed was a pure culture was in fact a tight syntrophic association between two distinct organisms. One termed the S-organism which oxidized ethanol to acetate with the liberation of hydrogen. The other organism, called Methanobacterium strain MOH, was an anaerobic methanogen that reduced CO2 to methane using the hydrogen liberated by the S-organism. The S-organism when isolated and grown independently on ethanol grows very poorly due to feedback inhibition caused by the accumulation of hydrogen. The association of the S-organism with strain MOH permits the luxurious growth of both.

Genetic Exchange and Lateral Gene Transfer

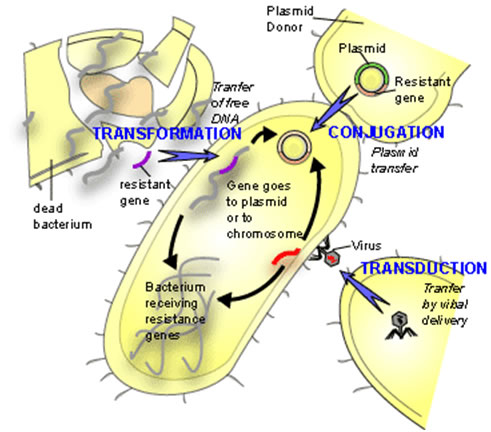

First discovered in 1928 by Frederick Griffith, lateral gene transfer is the process by which bacteria can pass genetic material laterally, from one bacterial cell to another rather than to descendent cells. Griffith showed that an extract from virulent but killed Streptococcus pneumonia cells when added to a living culture of nonvirulent S. pneumoniae could cause a proportion of these cells to become virulent in turn. The extract in question was, of course, DNA and this classic experiment demonstrated not only lateral (or horizontal) gene transfer (LGT) but also provided the first evidence for DNA as the genetic material. The mechanism described by Griffith is now termed Transformation and in this process, by mechanisms still not fully understood, living bacterial cells in a physiological state called competence take up foreign DNA across their cell membrane and incorporate it into their own genome by genetic recombination.

Since Griffith’s pioneering discovery of transformation, two other mechanisms of LGT have been discovered, these are conjugation and transduction.

Conjugation requires direct physical contact between the donor and the recipient cell. This contact is made by a tube called an F or sex pilus. The F-pilus is made of protein and is produced by the donor cell, which possess a genetic element called a tra (transfer gene cluster) operon. This gene cluster is typically contained on a small independently replicating circular piece of DNA called a plasmid. Although there are many types of plasmids in bacteria, which confer all manner of unique traits on cells possessing them (antibiotic resistance, heavy metal resistance, and virulence for example), this F plasmid directs the construction of the sex pilus by which an F bearing cell may attach to a cell lacking the F-plasmid. The pilus then contracts drawing the cells closer together. There is dispute as to whether the DNA passes through the F pilus or whether the pilus is only a mechanism to draw cells together and that DNA transfer is directly from cell to cell across the cell membrane. Babic et al. may have settled this question by demonstrating that cells, not directly in cell wall contact can still pass transfer DNA over considerable distances (ie. 12 mm). &mu

Ana Babic, Ariel B. Lindner, Marin Vuli, Eric J. Stewart, Miroslav Radman, 2008. Direct Visualization of Horizontal Gene Transfer, Science: 319. 1533 – 1536.

In transduction a bacterial virus or phage is mistakenly packaged with a piece of bacterial DNA. When this virus "infects" another bacterium at least a portion of the DNA introduced into the cell is bacterial not viral. Since the DNA transferred is less than the complete viral genome, the recipient cell survives and the bacterial DNA so introduced is available for inclusion in the bacterial genome either by recombination or by the integration of the bacterial virus into the host genome (lysogeny).

Each of these three mechanisms has in common the donor to recipient unilateral transfer of genetic material but they differ in the mode of DNA delivery. Transformation is limited by the exposure of native DNA to the external environment in which the molecule may be attacked by nuclease enzymes that can destroy its integrity. Conjugation is limited by the necessity for donor and recipient cells to come into close proximity with one another on the scale of a few tens of μm. Transduction requires the production of enormous numbers of virus particles only a small proportion of which will be defective and carrying bacterial DNA. Furthermore, only a small proportion of these so-called defective viruses will find susceptible host cells to infect.

Each of these limitations would seem to be lessened if the cells involved in the transfer were contained within a highly hydrated, viscoelastic mass, in other words a biofilm.

Some might argue that naked DNA, as required for transformation, would be especially vulnerable in a biofilm environment. The work of Cynthia Whitchurch and her colleagues suggests that far from being a hostile environment for isolated DNA, extracellular DNA may be an integral and necessary component of at least some biofilms (Pseudomonas aeruginosa for example). These investigators found that the matrix of P. aeruginosa biofilms contains significant amounts of DNA and that destruction of this DNA by Deoxyribonuclease resulted in the dissolution of young, although not of old, biofilms, indicating that extracellular DNA is a necessary structural component of the matrix of developing Pseudomonas biofilms. This observation, if general in scope, might indicate that the matrix environment is not as hostile to native DNA as one might think, a favorable circumstance for transformation.

Cynthia B. Whitchurch, Tim Tolker-Nielsen, Paula C. Ragas, John S. Mattick, 2002. Extracellular DNA Required for Bacterial Biofilm Formation, Science 295. 1487 ; | Next

In vitro research into each of the three mechanisms of LGT was initially carried out in liquid phase culture with subsequent identification of recombinant cells on selective media. Transformation in bacteria depends upon the recipient cells being in a state termed competence. Cells in this state are capable of taking up extracellular DNA with the eventual incorporation of a portion of this DNA into the host genome by genetic recombination. In many of the most common systems in which transformation has been studied it has been shown that competence is under the control of a process called Quorum Sensing (QS). QS is a phenomenon in which bacteria can chemically sense the presence of other bacteria and when bacterial populations become high enough, new suites of genes may be expressed. Small molecules produced by these bacteria are released into the surrounding environment and when the concentration of these compounds reaches a critical threshold they bind to RNA polymerase enzymes and initiate the transcription of genes formerly inactive. In a flowing environment, it seems likely that these small molecules would be washed away, in a biofilm, however, one might expect these small molecular weight compounds to accumulate resulting in DNA transcription. In Bacillus subtilus, Streptococcus mutans, S. gordonii and S. pneumonia QS is known to be involved in the induction of competence. It is also known that these organisms all participate in biofilm formation. In one investigation C. Vitkovitch (2004) demonstrated that biofilm grown Streptococcus mutans was transformed to erythromycin resistance either by the addition of naked DNA or heat killed donor cells carrying the antibiotic resistance genotype. The rates of transformation were 10 to 600 times greater than those observed in cells in planktonic culture. Young biofilms, 8 to 16 hours old, exhibited the highest rates of transformation but it was also shown that in biofilms of any age there were always competent cells present. Aside from demonstrating the capability of biofilms to undergo transformation, this experiment shows that the biofilm matrix is no barrier to DNA mobility.

Yung-Hua Li, Peter C. Y. Lau, Janet H. Lee, Richard P. Ellen, and Dennis G. Cvitkovitch, 2001. Natural Genetic Transformation of Streptococcus mutans Growing in Biofilms, Journal of Bacteriology, 183: 897-908

Conjugational transfer of a tetracycline bearing plasmid was demonstrated by Dunny in Enterococcus faecalis. The recipient strain, was established as a biofilm on glass rods in a biofilm reactor. Pre-grown donor cells were added to the reactor and the biofilms were harvested at various intervals with the cells being assayed for plasmid transfer on selective medium plates. Plasmid transfer in the biofilm system was observed to be 100 times higher than in planktonic culture. As was the case with transformation, plasmid transfer in conjugation was more effective in young biofilms with the rate declining as the biofilms became thicker (Dunny et al. 1995).

Dunny, G.M., B.A. Leonard, and P.J. Hedberg, 1995. Pheromone-inducible conjugation in Enterococcus faecalis: interbacterial and host-parasite chemical communication. J. Bacteriol. 177: 871-876.

The close association between microbes of many different species found in naturally occurring (non-laboratory) biofilms would seem to open the possibility of cross-species conjugation.

In fact, intergeneric conjugation has been observed in in vitro laboratory studies. In one example, a dual biofilm was created consisting of a Bacillus subtilus strain carrying a tetracycline resistant gene construct and a sensitive Staphylococcus species. After 6 and 24 hours, Staphylococcus isolates resistant to tetracycline were recovered and were shown to be carrying the identical tetracycline resistant gene originally borne by the Bacillus (Roberts et al. 1999).

Reports of transduction within biofilms are not as common as those of transformation or conjugation. Numerous reports exist of bacterial virus genes being expressed in biofilms. There are also examples of bacterial genes carried by bacteriophages being expressed in the cells of biofilms, but no clear examples of bacterial gene transduction have been reported (James Bryers, Personal communication). Nevertheless, given the ubiquity of virus infection in bacterial populations, and the ease with which bacterial viruses penetrate the matrices of biofilms, it would seem likely that transduction too is a common means of horizontal gene transfer in biofilms.

Resistance to Predation by Protozoa and Phagocytic Blood Cells

Motion pictures of neutrophiles attacking an established biofilm show them actively moving over the bacterial mass, "grazing" on the surface cells. Those cells deeper in the bacterial mass escape predation and later rapidly replace lost cells.

Video 1 shows human leukocytes flowing past a 7-day Staphylococcus aureus biofilm growing on the wall of a glass flow cell. Some of the leukocytes were entrapped in channels in the biofilm (white arrow). Flow was laminar. Time period=3 sec.

The failure of these phagocytic neutrophiles and macrophages to penetrate the EPS matrix, and clear the biofilm infection may result in what some refer to a frustrated phagocytosis (Costerton et al. 1999). The phagocytic cells frequently lyse, releasing a shower of pharmacologically active compounds, including hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion, hydroxyl radicals, singlet oxygen, hypochlorous acid and nitric oxide. These compounds, though toxic to planktonic cells, and cells enclosed in lysosomes, have much less effect on cells enclosed in biofilms. These compounds do however cause inflammation in normal tissue leading to the speculation that much of the damage caused by biofilms is due to the hosts inflammatory response to the infection rather than to the biofilm infection itself.

Costerton, J.W., P.S. Stewart, and E.P. Greenberg. 1999. Bacterial Biofioms, A Common Cause of Persistent Infections. Science, 284: 1318-1322.

The ubiquitous distribution of protozoa in the microbial habitat represents a significant selective factor in the evolution of bacteria perhaps leading to a variety of adaptations, including Altered cell surface receptor molecules, eukaryotic toxins (violacin), and the formation of biofilm consortia. Matz and Kjellberg argue that predation by free living protozoa may represent a major selective force in the evolution of biofilms.